(2015 - ongoing)

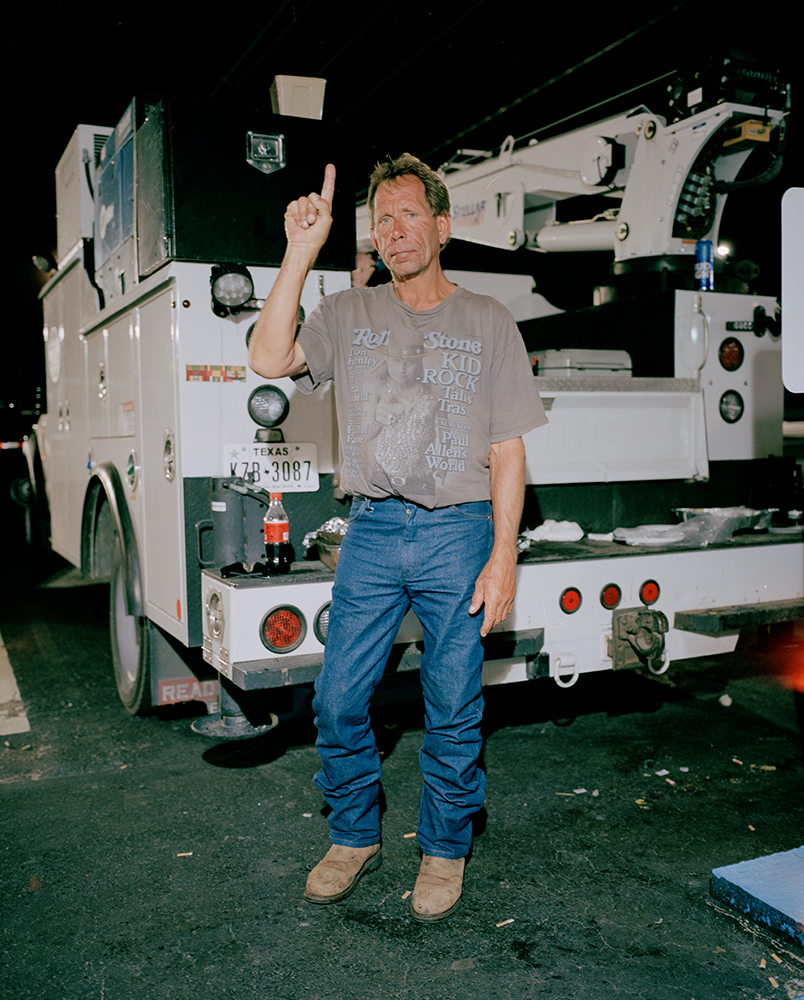

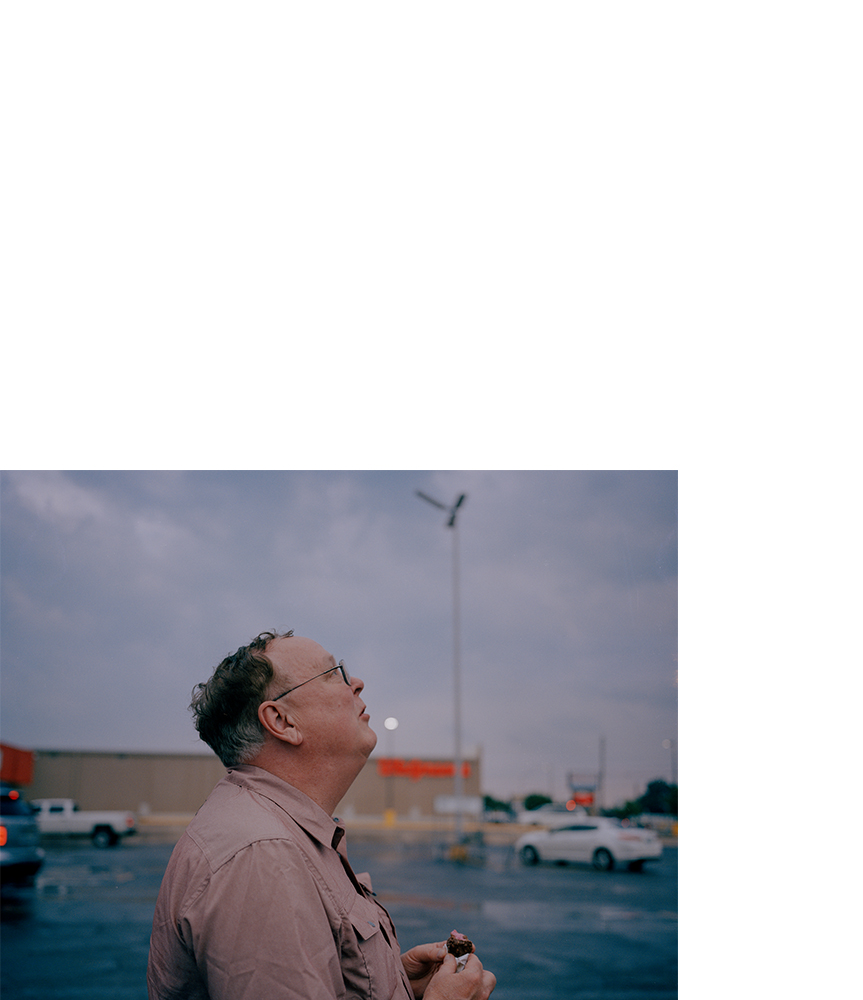

When I first get to Tornado Alley, meteorologist and tornado chase tour leader Charles Edwards, a gentle Christian bear of a man, picks me up from Norman, soaking wet from a minor flash flood. The next day, eighteen of us pile into three vans and head to Texas. In the weeks of driving that ensue, I get to know them. The demographic is largely white, male, and middle aged.

They have their idiosyncrasies - George, our driver, is the host of an adventure TV show and speaks only in soundbites. Olivier ‘Klipsi’ is on a mission to play his fiddle underneath various kinds of natural phenomena. Many aren’t satisfied with their desk jobs, they tell me. They are Neverland’s Lost Boys, reclaiming their freedom in Tornado Alley.

Stormchasing is nothing like Twister would have you believe. Rarely, if ever, do manic divorcé couples drive straight into a mile-wide tornado in a pickup truck while oil tankers explode left and right.

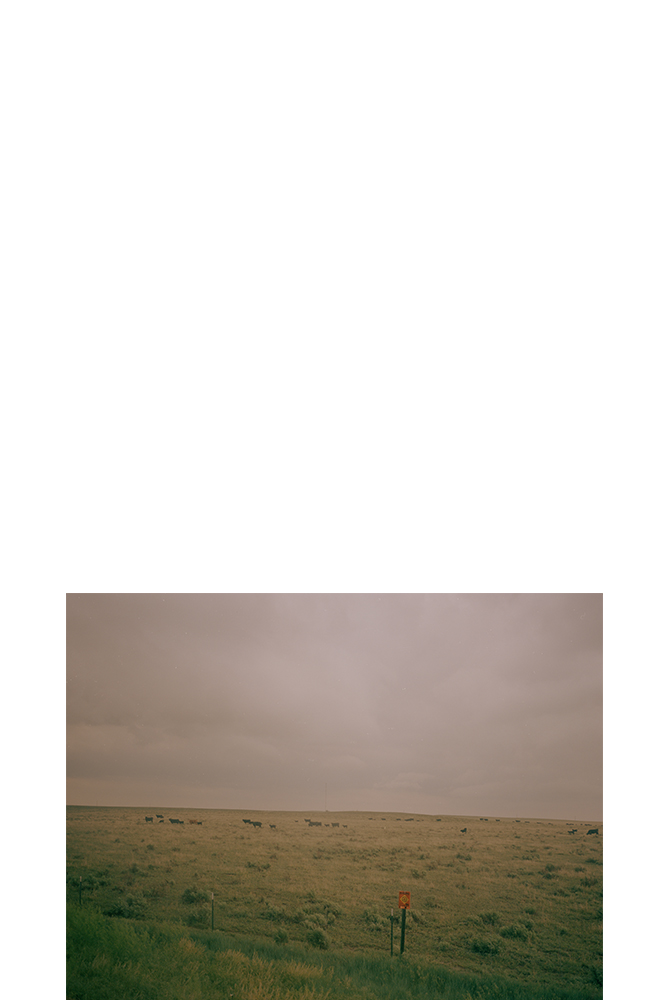

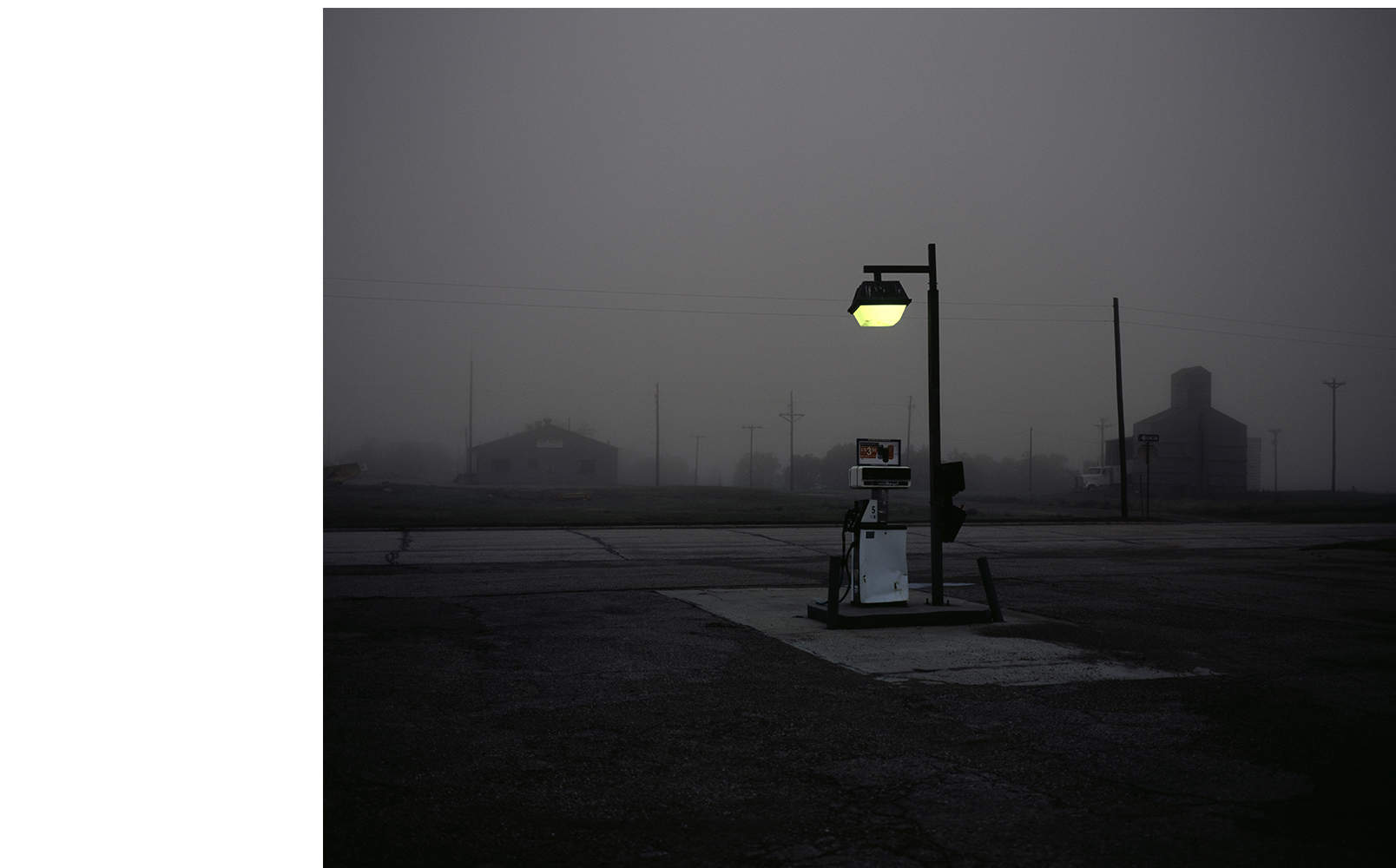

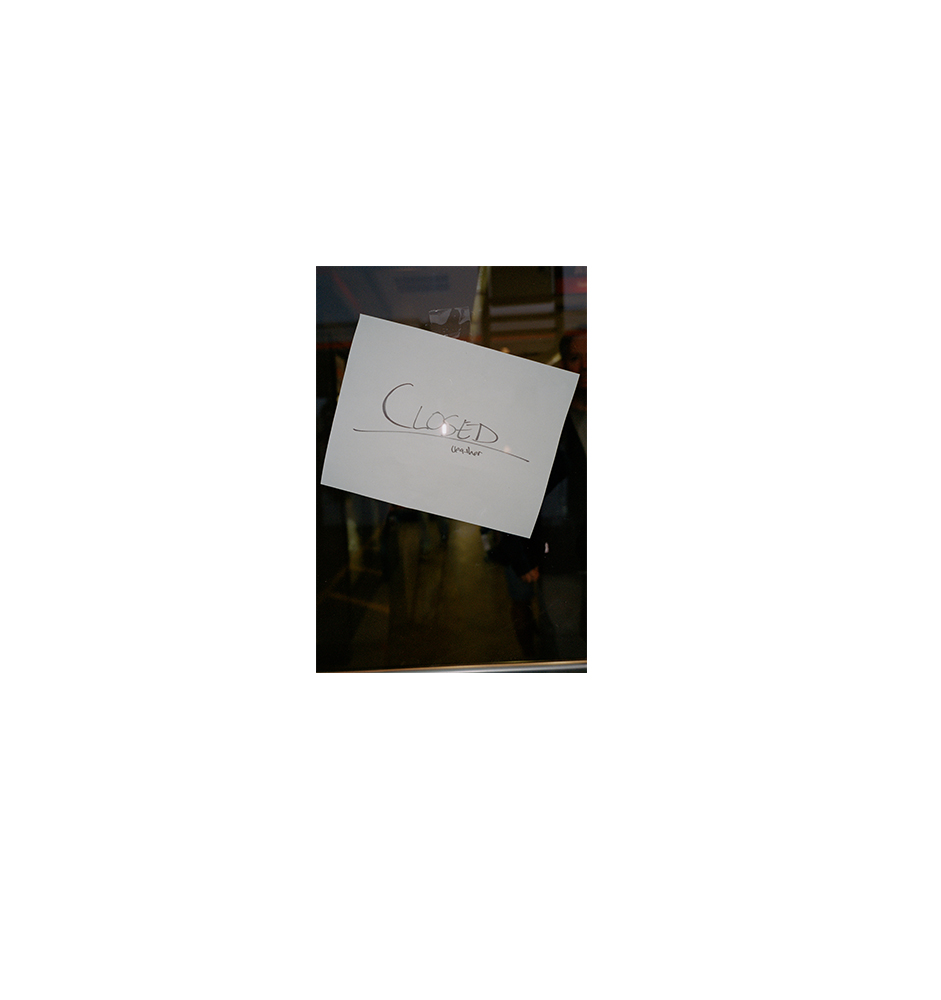

2019 was America’s fourth-most active tornado season on record, with over 1,500 confirmed events, but to see one is not the norm for most chasers. People wander the plains for years and never get close. The act of stormchasing, in my eyes, morphs into an endless wandering of a middle America that is steeped in myth and metaphor, into an indulgent metaphysical exercise in hunting down an ever-elusive Aetolian Boar.

There is a deep familiarity that runs in Chaser community. Separate teams regularly gather in small-town steakhouses to discuss the day’s events. Part of the camaraderie is based on a repertoire of crude middle-school humour and references to Twister, inside jargon, eating terrible gas station food for weeks, and making rude noises with silly putty. But it runs deeper than that. Charles’ daughter Emma was born while he was on a chase, a much-loved man called Chris died in his motel room last year.

Yet, tornadoes and severe storms have also torn down towns and lives since time immemorial. I meet Kenny, who understandably, loathes the sight of storm chasing vehicles crowding into town. His home in Greensboro, Kansas, was destroyed by a tornado in 2018 along with the rest of the town. Chasers can have the reputation of being insensitive, and endangering themselves and others by blocking roads, driving recklessly, and generally being a nuisance at the scene of potential tragedy.

I left Tornado Alley on the anniversary of the most infamous deaths of Chasers in recorded history - those of Tim Samaras and co. A respected scientist, known by almost everyone in my group in first or second person, he was killed in his vehicle in 2013 by a tornado known simply as ‘El Reno’ that unpredictably and randomly grew to 2.5 miles wide, with 295mph winds, and took a sharp left turn, in the span of a minute. Even today, when people ask me if chasing is dangerous, I assure them that it’s all pretty safely done if you know what you’re doing. But then I’ll remember El Reno, and that we really know nothing at all.

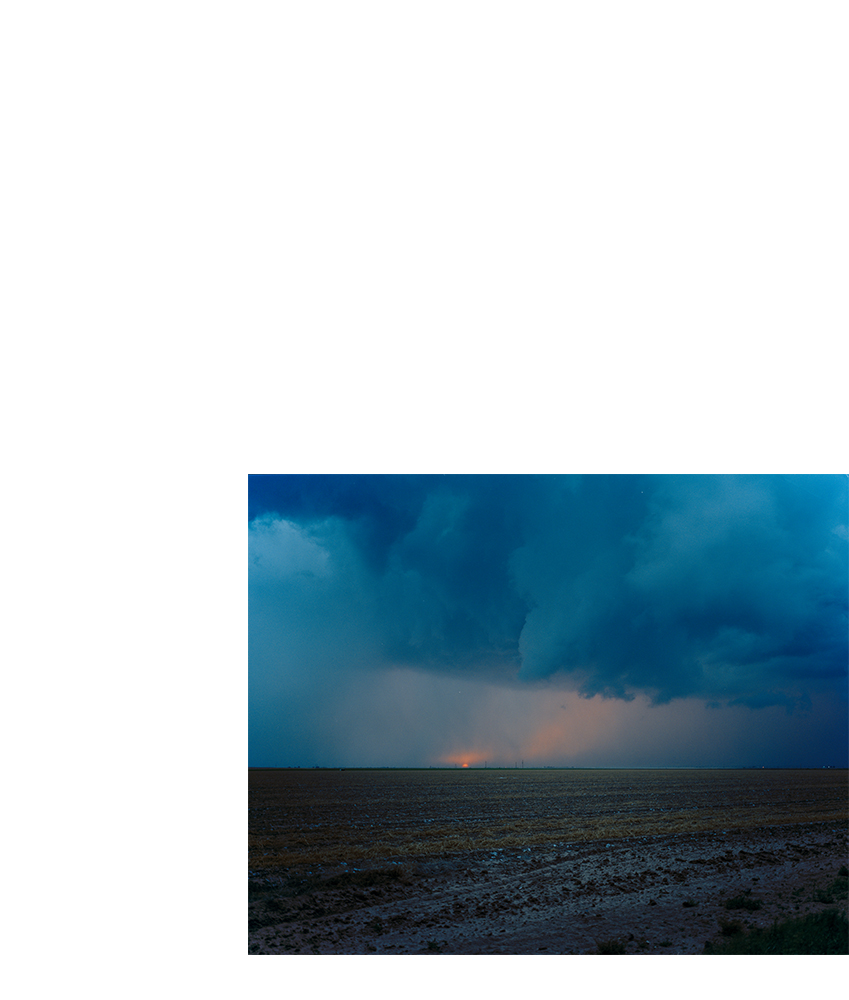

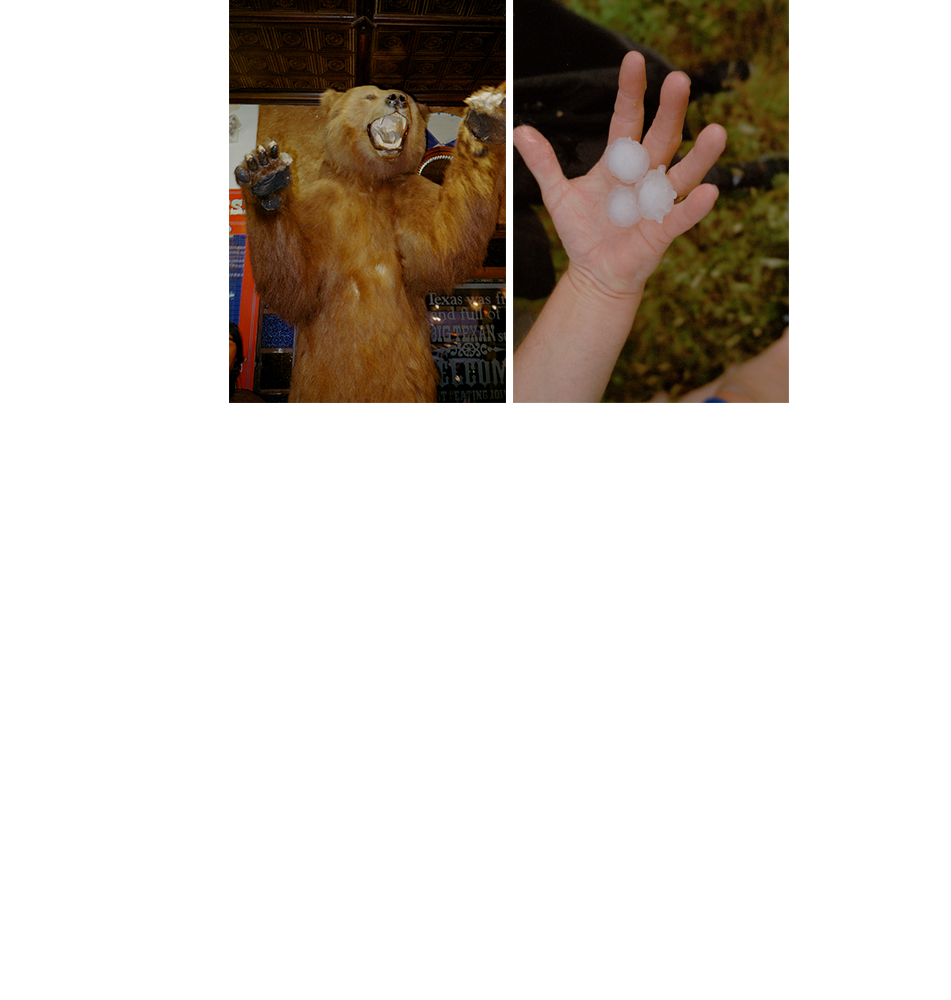

A supercell is a thunderstorm that is characterised by a ‘mesocyclone,’ which a rotating updraft of air that could spawn a tornado. They can cover hundreds of thousands of square miles and the clouds can develop up to sixty miles high. Driving toward a supercell feels like driving under an enormous spaceship. The adrenaline is unusually slow to build up. There is first a feeling that something is not quite right with the world. The sky turns an otherworldly green. The air smells unmistakably of petrichor. It is terrifyingly silent except for the electricity buzzing though the power lines and the rattle of hailstones churning in the clouds overhead.

Conversations will die out. Klipsi will hang up the phone with his mother in Switzerland. Once out of the van, you will see the clouds start to slowly spin like a carousel. The supercell will drop down a ‘wall cloud’ that I can only compare to a suction cup on an octopus’ tentacle. If conditions are right, this is the point where a funnel cloud struggles to drop. Your fight-or-flight instinct, i ffunctioning correctly, should tell you to rapidly get out of the way.

Toward the end of a chase last year, we found ourselves on the trail of a particularly promising supercell somewhere in Kansas, waiting outside a gas station. An unsuspecting man wandered out from the store, and took one look at us and the dancing weather vanes above our cars, the chicken wire hail protection, the scores of people looking animatedly at their phones and and talking in excited whispers. “I don’t know what the fuck’s going on here,” he said to me, “but it’s time for me to get the fuck outta here.” He drove off in the direction that we had come from. I looked up. The sky was still blue. But the chase was on.

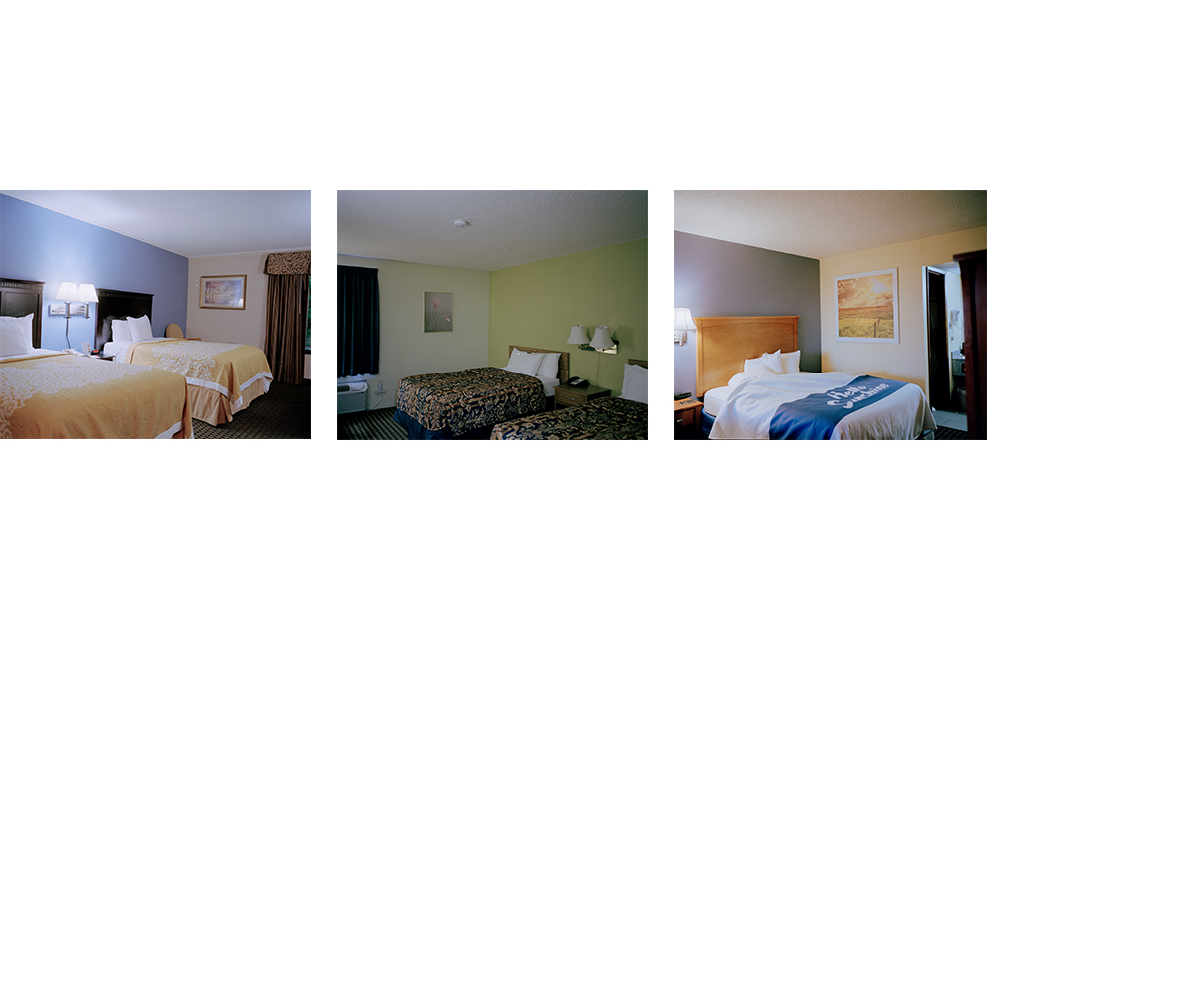

We must have driven through a hundred villages last spring, a troop of crazy people in reinforced-out jeeps tearing through Motels 6es. I remember miles of nothing, and then suddenly storefronts would pop up like jack-in-the-boxes in the scrubland. They were named ‘Beer’ or ‘Shotguns’ or ‘Beer and Shotguns.’ They were named ‘It’ll Do Motel’ and ‘Joe Bucks Coffee.’ And then suddenly they were gone.